The next control to be considered in putting together a proper exposure is the size of the hole in the lens, channeling light through to the recording surface, otherwise known as the aperture.

As you focus this hole in the lens is at its maximum so as you look through the camera you will be able to see everything nice and bright. When you depress the shutter a control closes the aperture blades producing a hole to the chosen size, then reopens it when the shutter closes.

The aperture, coupled with the shutter speed governs the amount of light being allowed to reach the recording surface.

The sizes of the hole in the lens are a standard set, referred to in the following scale: f/1.4, f/2, f/2.8, f/4, f/5.6, f/8, f/11, f/16, f/22, and f/32.

Modern-day lenses also have apertures measured in third stops as well. For the purposes here, we will keep to the standard scale above for ease of understanding. The hole in the lens is represented by the different numbers listed above, with f/1.4 being the largest hole while f/32 the smallest hole. There are lenses with even bigger holes available and some with even smaller holes but for general purposes, these are common numbers.

A lens is referred to by its widest maximum aperture. For example, you may purchase a 50mm lens with its widest maximum aperture being f/1.4. Some people make reference to this widest maximum aperture as the “speed” of the lens, an example, “I have a 70-200mm f/2.8 lens.” This will be on the lens, usually at the front where the lens focal length is listed.

Some lenses have a variable maximum aperture that you should be aware of. Zoom lenses in particular may have a maximum aperture of say f/4-f/5.6. Let’s say that this is on a 70-210mm lens. What that means is that at 70mm, the lens has its widest maximum aperture at f/4 while as it zooms, usually towards the end at 210mm, the lens’s widest maximum aperture becomes f/5.6, you lose 1 stop.

Besides governing the amount of light coming into the camera and striking the recording surface, the aperture also affects the depth of field in the photograph, the amount of the subject that will appear to be in focus. Some refer to it as depth of focus and some of the effects have even been referred to as selective focus.

A wide aperture, f/1.4 for example, will allow for little depth of field where your subject may be in focus, but, things just in front of and behind are out of focus. A smaller aperture, f/22 for example, will see more in front of the subject and behind the subject in focus. There are several rough rules of thumb that apply to choosing your aperture. A quite simple one includes: if you want to see it all, use a small aperture such as f/22 and if you only want to see only your subject, use a wider one, such as f/5.6.

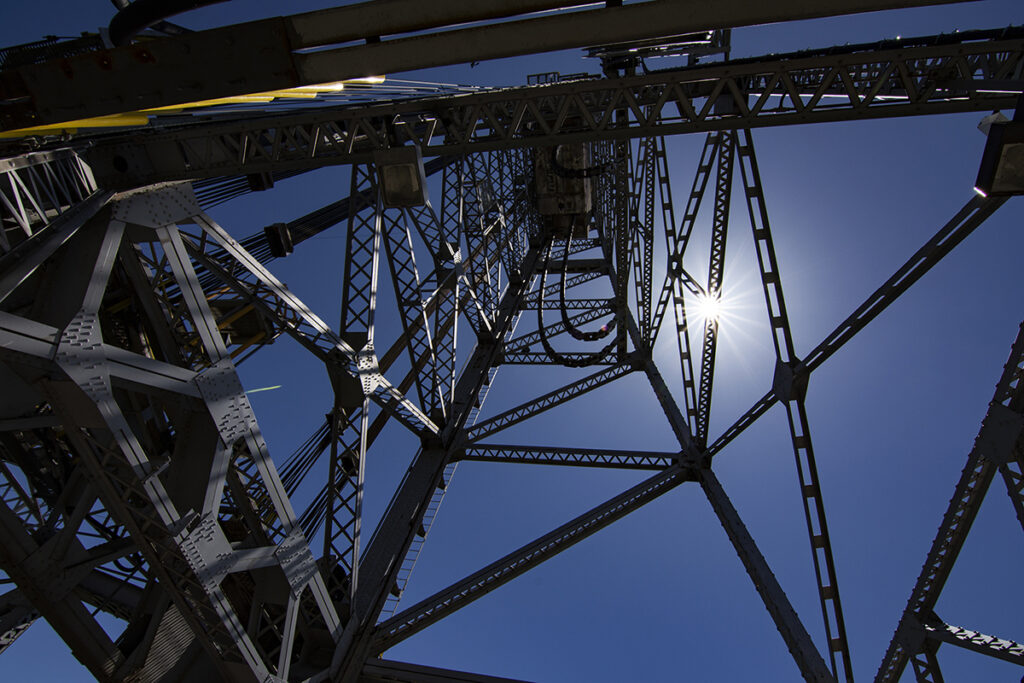

Using a small aperture to produce more depth of field is very common in landscape photography where you want to see as much in focus as possible. It’s also common when going for this effect to use a tripod as slow shutter speeds are likely going to happen.

When using a wider aperture, photographers are trying to isolate a subject against a busy background which can include sports photographers at vehicle races or portrait photographers who want to isolate their subjects from the background ensuring that the main subject is sharp and the other details aren’t crisp.

Once you have chosen the aperture that you want to use for your subject, the next part is to choose the appropriate shutter speed to ensure proper exposure as per the camera’s built-in exposure meter. Keep in mind that certain shutter speeds can mean that you need to use a tripod to ensure that there is no camera shake or vibration from depressing the shutter. Also keep in mind that with certain apertures, especially when you are trying for lots of depth of field, you may get into slow shutter speeds producing motion action in the photo, depending on the situation and subject matter.

Other things that can affect your depth-of-field are lens choice and how close you are to your subject, but, we’ll discuss that at a later time.

Next

Setting your ISO sensitivity

Putting it all together, coming up with a proper exposure